What does the future hold? Our enduring fascination with predicting the future is reflected on the silver screen, as excitement builds over the Blade Runner sequel. We continue being mesmerized by ancient prophecies, such as Nostradamus' Quatrains. And we certainly pay very well to pundits, economists, and intelligence analysts who try to predict coming social, economic, and political events. Unfortunately, this abiding interest in prediction has not translated into the ability to forecast future events with much accuracy. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, left-leaning social theorists envisioned a future in which societies were self-organized, and countries, religions, and private property were relics in the rubbish heap of history. Twentieth-century futurists envisioned a 21st century entirely different from the one we inhabit, including flying bicycles as the predominant means of transportation and permanent lunar colonies by the year 2000. Such futurists and social theorists are in good company. Even professionals, whose job description consists of forecasting future social trends, on the whole, do little better than lay people at predicting future geopolitical events. In fact, neither experts nor lay people do much better than chance (Tetlock, 2006; Tetlock & Gardner, 2016). As the seminal science fiction author Isaac Asimov -- inventor of the fictional discipline of psycho-history -- pointed out, there seems to be little hope for a real science of the future.

A portrayal of the future from the 1982 film Blade Runner depicting Los Angeles in 2019. Flying cars, androids, anonymity and omnipresent advertising. Some of these visions have come to fruition, most have not. Source: https://www.warnerbros.com/sites/default/files/blade_runner_background1.jpg

But there may be some hope after all. In our view, modeling cultural change on a large scale using cross-temporal data and theories derived from behavioral ecology can usher in a new era in social psychological and personality research. We have the potential to shift from explaining the past to predicting the future. This new approach to cultural change has led not only to the discoveries we report below, but also has fundamental implications for psychometric assumptions and replicability in psychological science. We discuss these ideas in depth in our article published online ahead of print in Perspectives on Psychological Science (Varnum & Grossmann, 2017), and we highlight key contributions and promises of the emerging psychology of cultural change in the present piece.

To predict the future, we first have to understand the past. To do so, our research group and others have begun to conduct systematic research aimed at identifying the patterns of cultural change across a wide range of psychological phenomena. For example, we now know that over the past several decades, self-esteem, narcissism, and intelligence have increased in many Western societies (Twenge & Campbell, 2001; Twenge, Konrath, Foster, Campbell, & Bushman, 2008; Flynn, 1984; Trahan, Stuebing, Fletcher & Hiscock, 2014), whereas social capital (e.g. involvement in civic organizations and voter turn-out) has been on the decline (Putnam, 1995; 2000). More recently, our research group has found that over the past 60-70 years gender equality has been on the rise in the Western world (Varnum & Grossmann, 2016) and that individualist attitudes, practices, and relational patterns have increased across more than 60 countries around the globe (Grossmann & Varnum, 2015; Santos, Varnum & Grossmann, 2017).

The idea that cultures are not static and do change is not novel. At least since Kurt Lewin and Lev Vygotsky, theorists have pointed out that psychological phenomena unfold within a temporal context. What is unique is a rigorous theory-driven attempt to not only document but to test explanations for patterns of societal change empirically. This emerging work suggests that among the most powerful contributors to cultural changes in areas like individualism, gender equality, and happiness are shifts in essential features of our ecologies. The idea that variations in ecological dimensions and cues like scarcity or population density might be linked to behavioral adaptations has been widely explored in the animal kingdom, and recently started to gain prominence as a way to explain variations in human behavior (Ellis, Bianchi, Griskevicius, & Frankenhuis, 2017; Sng, Neuberg, Varnum, & Kenrick, 2017). As we detail below, insights from behavioral ecology, along with statistical tools common to the field of econometrics, have enabled greater rigor and precision in understanding the causes of cultural change.

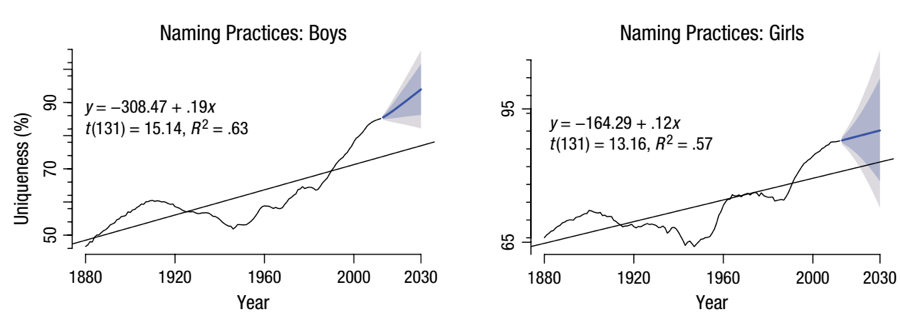

Individualism/Collectivism: A few years ago we wondered whether we might be able to use ecology as a way to understand rising individualism - - an increased focus on uniqueness and independence and emphasis on self-expression - - in the United States. To do so, we gathered data from numerous sources, ranging from national census surveys to types of words used in Google books, to preferences for relatively unique vs. common baby names for one’s children. Simultaneously, we aggregated country-level data concerning several theoretical explanations of why societies may become individualist or collectivist, including resource scarcity, climatic stress, urbanization, frequency of natural disasters, and the prevalence of infectious diseases. Next, we used cross-lagged statistical models to evaluate the magnitude and direction of the effects: Do shifts in individualism occur before or after possible shifts in respective ecological indicators? Using cross-correlation functions and tests of Granger causality we started to unpack these relationships. As it turned out, a shift toward greater affluence and white- (vs. blue) collar occupations was the most robust ecological predictor of levels of individualism over time, further shifts in levels of SES consistently preceded changes in levels of individualism in America (Grossmann & Varnum, 2015) – a finding that has since been extended and cross-validated by our team in a study examining the rise of individualism around the globe (Santos, Varnum, & Grossmann, 2017).

Changes in baby naming practices in the US from the 1880’s to the 2010s and predictions for future trends through 2030. Adapted from Grossmann and Varnum (2015).

Gender Equality: Next we turned to another marked cultural change in recent decades -- shifts in gender equality. The US has seen an increase in gender equality in the past several decades. This shift has been reflected in changes in laws and policies, greater representation of women in high-status professions and roles (including government), and shifts in social attitudes regarding gender. When we think about why our society may have become less sexist, social movements (like Women's Liberation), laws (like Title 9), landmark legal rulings (like Roe v. Wade), and medical advances like contraception all come readily to mind. Though these events all likely have played a significant role, we suspected that here too subtle shifts in our ecology might play a role in this cultural shift. Once again, we aggregated time series data concerning gender equality (e.g., male/female wage ratio, political representation, pronoun use in books and sexist work attitudes) and numerous social-ecological factors in the US and used a variety of statistical techniques to assess the strength and direction of relationships between various ecological dimensions and levels of gender equality. It turned out that a decline in levels of infectious disease was the most robust factor predictor of rising gender equality, a finding we were able to replicate in the UK, and in both societies we found evidence that changes in pathogen levels preceded shifts in gender equality (Varnum & Grossmann, 2016).

Happiness: Independently, other scholars have explored changes in levels of subjective well-being over time. Research examining affect in books and newspaper articles over a 200-year span shows a long-term decline in American happiness (Iliev, Hoover, Dehghani, & Axelrod, 2016). Levels of well-being in these studies appeared linked to Okun’s Misery Index, an economic indicator that combines unemployment and inflation rates (Iliev et al., 2016), consistent with the idea that scarcity or abundance of resources matters for happiness. Another study exploring the cause of changes in levels of well-being over time in the US found strong links to levels of economic inequality, suggesting that happiness decreases as inequality increases (Oishi, Kesebir, & Diener, 2011), suggesting that not only absolute levels of resources but their distribution in an environment (what behavioral ecologists call “resource patchiness”) help to explain changes in well-being over time.

So how can we use these findings and this emerging field to predict what our societies may look like in 2047 or 2117? We believe that an integration of current theories, and methods from cultural change research (i.e., ecological framework, big data, and econometric tools) along with insights from machine learning may enable a genuinely predictive science of cultural change. In fact, data from the studies described above may serve as a starting point for efforts to develop robust predictive models and to assess the ability of such models to predict future cultural changes. Beyond helping us to understand why cultural shifts occur in phenomena like individualism or gender equality, such an integration could help us to anticipate what our societies may look like in the future.

The emerging science of cultural change is likely to be of broad interest both inside and outside academia, appealing to behavioral scientists, policymakers, and the general public. But what if you are a social or personality psychologist and not interested in cultural change per se, why should this work matter to you?

We can think of several reasons. First, we all study samples embedded in a particular socio-cultural context. Most samples we collect are “WEIRD,” consisting largely of white American middle-class college students who it turns out are not psychologically representative of humanity (Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010). But perhaps more importantly emerging insights from the cross-temporal study of psychological processes suggest that as psychologists, whether we are aware of it or not, we are studying a moving target. There is no guarantee that the structure of psychological constructs (and their relationship to each other) remains consistent over time – a critical insight for anybody studying individual differences or the interaction of the social context and personality.

Second, in behavioral and management sciences that focus on cross-cultural comparisons, we need to ensure that our measurements are made contemporaneously. One widely used set of variables in cross-cultural psychology and management research comes from Hofstede’s work identifying key dimensions of cultural variation (Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, 2010), yet it turns out that country-level scores in many societies were calculated from data collected decades apart! Researchers should be wary of using such indicators in the future, given what we know about cultural changes in dimensions like individualism over the past half-century.

Third, for those interested in the ways socio-cultural context impacts human minds, the new field of cultural change enables better tests of theories regarding the origin and evolution of cross-cultural variations than the cross-sectional approaches that are currently standard in the field. Time series data permit stronger inferences regarding the causes of cultural variation than is possible from datasets where putative causes and outcomes are measured only once and at the same time.

Finally, our emerging field may have some implications for debates about replicability (Greenfield, 2017; Varnum & Grossmann, 2017). This is not to say that cultural change is likely the explanation for many or most failures to replicate previous findings, but when there is a large temporal remove between the original studies and replication attempts, it may be wise to consider this when interpreting any discrepancies or changes in effect sizes.

We hope that most social and personality psychologists will be genuinely interested in integrating insights about cross-temporal change into their models of human behavior. As a field, we should not ignore the increasing availability of massive-scale data on human behavior and ecology, and the refinement of econometric and machine-learning forecasting tools. Using them wisely, we may one day move from an explanatory to a predictive psychological science (Yarkoni & Westfall, 2017).

By Igor Grossmann and Michael E. W. Varnum

References:

Ellis, B. J., Bianchi, J., Griskevicius, V., & Frankenhuis, W. E. (2017). Beyond risk and protective factors: An adaptation-based approach to resilience. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(4), 561–587. http://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617693054

Flynn, J. R. (1987). Massive IQ gains in 14 nations: What IQ tests really measure. Psychological Bulletin, 101(2), 171 – 191. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.101.2.171.

Greenfield, P. M. (2017). Cultural change over time: Why replicability should not be the gold standard in psychological science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(5), 762-771. doi: 10.1177/1745691617707314

Grossmann, I. & Varnum, M. E. W. (2015). Social structure, infectious diseases, disasters, secularism, and cultural change in America. Psychological Science, 26(3) 311-324. doi: 10.1177/0956797614563765

Henrich, J., Heine, S.J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33, 62–135. doi:10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (revised and expanded). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill I

liev, R., Hoover, J., Dehghani, M., & Axelrod, R. (2016). Linguistic positivity in historical texts reflects dynamic environmental and psychological factors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S.A, 113(49), 7871-7879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1612058113

Oishi, S., Kesebir, S., & Diener, E. (2011). Income inequality and happiness. Psychological science, 22(9), 1095-1100. doi: 10.1177/0956797611417262

Putnam, R. D. (1995). Bowling alone: America's declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6(1), 65-78.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. In Culture and politics (pp. 223-234). Palgrave Macmillan US.

Santos, H. C., Varnum, M. E. W., Grossmann, I. (2017). Global increases in individualism. Psychological Science. doi: 10.1177/0956797617700622

Sng, O., Neuberg, S. L., Varnum, M. E., & Kenrick, D. T. (2017). The crowded life is a slow life: Population density and life history strategy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(5), 736 754. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000086

Tetlock, P. E. (2006). Expert Political Judgment. How Good Is It? How Can We Know? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Tetlock, P. E., & Gardner, D. Superforecasting: The art and science of prediction. Broadway Books.

Trahan, L. H., Stuebing, K. K., Fletcher, J. M., & Hiscock, M. (2014). The Flynn effect: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 140(5), 1332 - 1360. doi: 10.1037/a0037173

Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2001). Age and birth cohort differences in self-esteem: A cross-temporal meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(4), 321-344. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0504_3

Twenge, J. M., Konrath, S., Foster, J. D., Keith Campbell, W., & Bushman, B. J. (2008). Egos inflating over time: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality, 76(4), 875-902. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00507.x

Varnum, M. E. W. & Grossmann, I. (2017). Cultural change: The how and the why. Perspectives on Psychological Science. doi: 10.1177/1745691617699971

Varnum, M. E. W. & Grossmann, I. (2016). Pathogen prevalence is associated with cultural changes in gender equality. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(0006). doi:10.1038/s41562-016-0003

Yarkoni, T., & Westfall, J. A. (2017). Choosing prediction over explanation in psychology: lessons from machine learning. Perspectives on Psychological Science. doi: 10.1177/1745691617693393