If I asked you to evaluate the quality of your life, you would probably take your recent emotional experiences and moods into account to decide how well your life is going. The better we feel and the happier we are, the better we say our life is.

However, research suggests that culture plays a role in the strength of the relationship between emotional experience and life satisfaction. The connection between experienced emotion and reported life satisfaction is stronger in individualistic than in collectivistic countries, indicating that emotional experiences matter more to people in certain cultures than in others.

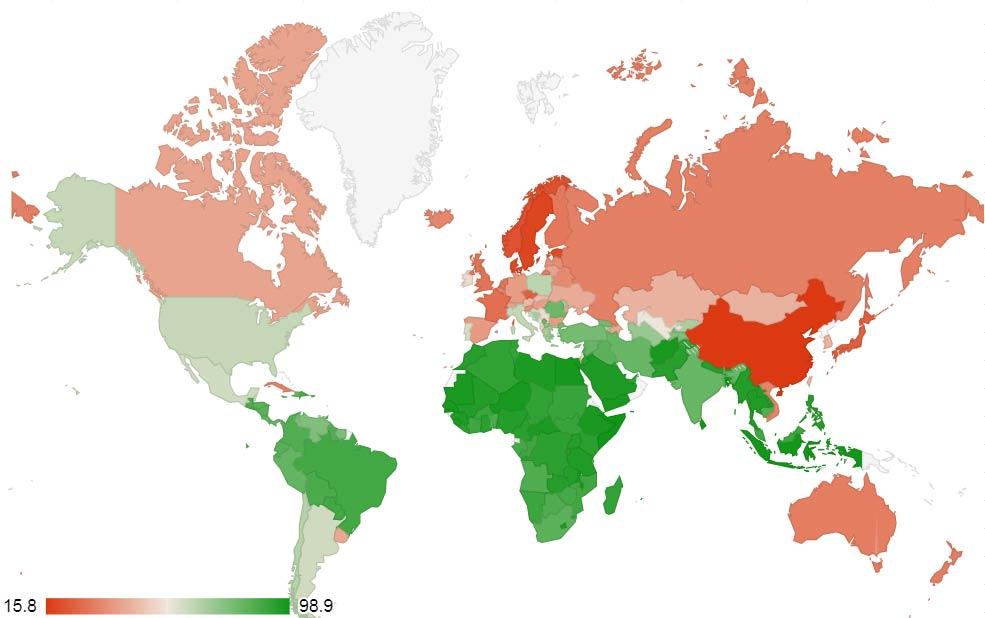

I decided to explore this connection more deeply by examining data from many more countries than have been studied previously and taking a look at a variable that has slipped our attention to date: religiosity. As shown in the map below, the percentage of people who report that religion is an important part of their lives varies substantially across countries, from 15.8% in China to 98.9% in Somaliland. (Deeper shades of green indicate greater national religiosity, and deeper shades of red indicate lower religiosity.)

Does the religiosity of a country make a difference with regard to the importance that people place on emotions in judging the quality of their lives? Reviewing psychological and sociological data as well as historical records suggests that it might. Researchers have found that emotions and well-being are interpreted and valued differently depending on the religiosity of their country. In highly religious cultures, psychological well-being is predominantly linked to the attainment of godly virtues and commitment to religious lifestyles, and pleasurable experiences are largely considered irrelevant as independent indicators of well-being.

The emphasis on emotions as an indicator of well-being is a somewhat recent cultural trend in the history of human civilizations. During the 17th century, the importance of good feelings slowly began to replace the old doctrines of salvation, and people began to judge their lives more in terms of how they feel on a daily basis. However, religious cultures are likely to be less influenced by these cultural trends. As a result, we might expect that emotional experience predicts life satisfaction more strongly in secular nations than in religious nations.

In my research, published in the journal Emotion, I examined a sample of 295,933 individuals from 147 countries, collected by the Gallup organization. The participants answered questions about their general life satisfaction, the importance of religion in their lives, and their emotional experiences, such as experiences of enjoyment and sadness. For each country, I calculated a national score of religiosity based on the percentage of people who reported that religion is an important part of their daily lives.

As I expected, people’s emotional experiences were more strongly related to their general life satisfaction in secular countries than in religious countries. Furthermore, this finding was replicated separately for Christians and Muslims, the two religions for which there were enough adherents across countries to conduct separate analyses. This means that emotional experience has a stronger effect on people’s life satisfaction in more secular (less religious) countries, and this pattern occurs for people of different religions.

One possible explanation for the finding that emotions are less important for life satisfaction in religious countries is that emotions are simply less common in these countries. However, people in religious countries reported higher levels of negative emotions than people in secular countries, so the results cannot be explained by suggesting that religious countries are generally less emotional than secular ones. Furthermore, the importance of positive and negative emotions as determinants of life satisfaction did not depend on how frequently people in each country experienced emotions overall.

Emotions are less important determinants and signifiers of well-being in religious countries because these countries are less affected by the modern norms and values that promote secularized concepts of well-being and emotion. People in more religious countries are more likely to evaluate their lives based on religious standards, such as the degree to which they live according to religious norms or participate in religious activities. In fact, some religions teach their adherents to find meaning even in negative emotional experiences and to avoid basing their happiness solely on positive feelings. A happy feeling may be considered sinful if it is not consistent with religious teachings.

For Further Reading

Joshanloo, M. (2019). Cultural religiosity as the moderator of the relationship between affective experience and life satisfaction: A study in 147 countries. Emotion, 19(4), 629-636. doi:10.1037/emo0000469

Zevnik, L. (2014). Critical perspectives in happiness research: The birth of modern happiness. New York, NY: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-04403-3

About the Author

Mohsen Joshanloo is an Associate Professor of psychology at Keimyung University, South Korea.