Have you ever met someone and thought something like “you aren’t quite a Kate, much more of a Noelle”? Or perhaps you’ve been on your way to meet someone named Kurt, and immediately had an idea of what Kurt would be like? How does this happen? Why do we form expectations about people based on the sound of their names?

Let’s take a step back and think about what language is. Fundamentally, language is a set of sounds we combine into words. Those words then refer to something, or someone, in the world. Importantly, these language sounds have unique features: they sound different, and they feel different. For example, the sound /n/ in Noelle sounds and feels very different than the sound /k/ in Kate. And it makes sense that these different sounds and feelings might evoke different associations, just like brighter colours might evoke different associations than darker ones.

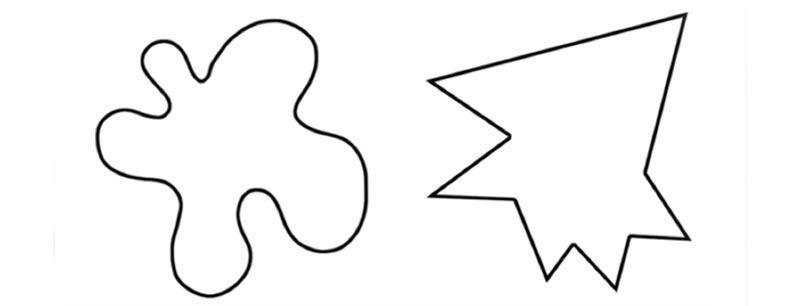

The finding that different language sounds evoke different associations is known as sound symbolism. A well-known example of this is the maluma/takete effect first described by Köhler in 1929. Imagine that an alien language has words for the two shapes below. One is a maluma, and one is a takete. Which one do you think is a maluma, and which do you think is a takete? you’re like 90% of people worldwide, you probably said that maluma is the round shape and takete is the sharp-edged shape. People tend to associate “sonorant consonants” such as /m/, /n/ or /l/ with round shapes, and “voiceless stop consonants” like /p/, /t/ or /k/ with sharp shapes.

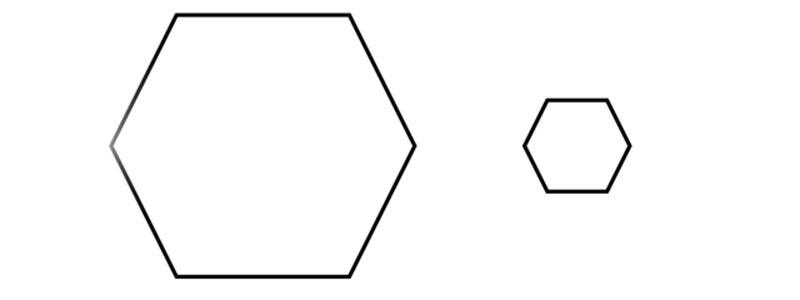

Another example is the mil/mal effect. Imagine that same alien language calls one of the shapes below a neep and one a nawp. Which is which? Most people tend to associate “high-front” vowels like the /i/ sound in neep with small shapes, and “low-back vowels” like that /ɑ/ sound in nawp with larger shapes. What sound symbolism shows is that the sounds in language can evoke certain associations, such as shape or size.

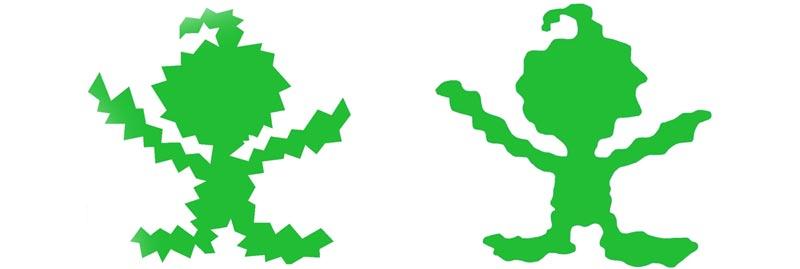

But let’s get back to names. In a 2015 study, we tested whether the maluma/takete effect extends to real first names. Sticking with the alien theme, we asked participants to give real names to aliens. They chose which of the alien shapes below would be more likely to be named Noel vs. Kurt or Molly vs. Kate. We found that participants tended to give names containing sonorant consonants, like Noel and Molly, to the round-shaped alien and gave names containing voiceless stop consonants, names like Kurt or Kate, to the sharp-shaped alien. This finding showed that sound symbolism can have an effect not only with invented words like muluma and takete but also with real names like Kurt and Molly.

While most sound symbolism research has focused on perceptions of physical properties such as shape or size, we were curious whether language sounds might also evoke associations to certain personality traits – such as “kind” or “outgoing.” So, together with Kristen Deschamps and Joshua Bourdage, we asked people to judge the likelihood that strangers with different first names would have certain personality traits.

The strongest finding was that people with sonorant names (such as Noelle) were judged to be higher in the trait of Agreeableness. This effect was found in all three of the experiments we conducted. In addition, in two of the experiments, we found that people with sonorant names were judged to be higher in Emotionality and Conscientiousness, and that voiceless stop names (such as Kate) were judged to be higher in Extraversion. In other words, people expect someone with a name like Noelle to be agreeable, emotional, and conscientious; and a person with a name like Kurt to be extraverted.

Although people seemed to have expectations about what people with different names might be like, we were curious to know whether their expectations reflected reality. For example, maybe people named Noelle really are nicer than people named Kate. So, we collected personality scores from over 1000 people and looked to see if the sounds in their names reflected their self-reported personalities. They did not.

This finding is informative because it shows that research participants’ reactions to the names were due to the sounds of the names themselves, rather than to the personalities that people with these names actually have. We also observed the same effects for the sounds of names that people had never seen or heard: the effects of sonorant vs. voiceless stop names on participants’ assumptions about people’s personalities were observed even when participants rated invented names such as Loenne or Keek.

So why do people make these associations? The maluma/takete effect is sometimes explained through metaphor: the smoother sounds in maluma have something metaphorically in common with the smoother round shape. Something similar may be happening when people’s names affect the inferences we draw about their personalities. For example, the smoother sounds in Noelle might have something metaphorically in common with a kind and easy-going personality.

Names are one of the cues we use to form impressions of other people, and our research shows that sound-based associations drive some of these impressions, both in terms of what people look like and their personalities. This may mean that people have your agreeable and hard-working personality in mind when they say, “You seem like more of a Noelle.”

For Further Reading

Dingemanse, M., Blasi, D. E., Lupyan, G., Christiansen, M. H., & Monaghan, P. (2015). Arbitrariness, iconicity, and systematicity in language. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19, 603-615.

Lockwood, G., & Dingemanse, M. (2015). Iconicity in the lab: A review of behavioral, developmental, and neuroimaging research into sound-symbolism. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1246.

Sidhu, D. M., & Pexman, P. M. (2018). Five mechanisms of sound symbolic association. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 25, 1619-1643.

Sidhu, D. M., & Pexman, P. M. (2019). The Sound Symbolism of Names. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28, 398-402.

Styles, S. J., & Gawne, L. (2017). When does maluma/takete fail? Two key failures and a meta-analysis suggest that phonology and phonotactics matter. i-Perception, 8, 2041669517724807.

David Sidhu is a cognitive psychologist who studies sound symbolism, embodied cognition, and language processing. Penny Pexman is a cognitive psychologist who studies how children and adults derive meaning from language.