When we meet someone for the first time, we notice a lot about them: we notice their gender, their race, how old they are, and often much more. And in general, what we notice about a person can be consequential. For example, learning that a person is Black rather than White, or a man rather than a woman, can influence our perceptions of that person’s competence.

Psychologists have recently pushed this topic even further, asking how perceptions of a person might depend on multiple aspects of who they are, for example, on their race and their gender. In some recent research, Galen Bodenhausen and I asked a question of similar flavor: Do the racial stereotypes we apply to a person depend on that person’s sexual orientation? According to our results, the answer is “yes.”

We conducted a series of experiments, all in the United States, where we asked people to list their beliefs about men from various racial groups. Some people told us what they thought Black men were like, other people told us what they thought Asian men were like, and still other people told us what they thought White or Hispanic men were like.

The people who participated in these experiments had pretty strong stereotypes in their heads. White men, according to their responses, were arrogant and nationalistic. Black men, also according to their responses, were athletic and aggressive. Asian men were quiet and hardworking, and Hispanic men were religious and uneducated. But here’s the thing: the participants who listed these stereotypes were very likely thinking of heterosexual men.

When participants were instructed to list their beliefs about men who were described as gay, their racial stereotypes changed in at least two big ways. First, participants tended to characterize gay men as possessing de-racialized attributes. Second, participants tended to characterize some gay men—in particular gay Black and Hispanic men—as possessing “Whiter” attributes as well.

By “de-racialized,” I mean that when men were described as gay (vs. not), they were characterized by traits that seemed less stereotypic of their own racial groups. How do we know these traits were less stereotypic? We gave a new group of participants the traits we’d collected earlier, and we had this new group of people rate these traits on how race-typical they seemed. Specifically, these new participants rated the traits on how stereotypically Black they seemed, how stereotypically White they seemed, how stereotypically Asian they seemed, and how stereotypically Hispanic they seemed.

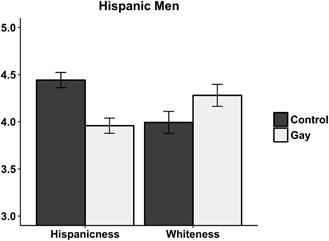

As an illustration, here’s what we found regarding the “Hispanicness” and “Whiteness” of the traits people listed about Hispanic men (depicted in dark gray) and about gay Hispanic men (depicted in light gray).

On the left-hand side of the image, you can see that Hispanic men were de-racialized, or rendered less stereotypic of their ethnic group, when they were described as gay (vs. when they were not). We found this pattern for all racial groups: White men seemed “less White” when they were described as gay, Black men seemed “less Black” under these same conditions, and Asian men seemed “less Asian” (when described as gay) as well.

We think that de-racialization occurs because, by default, people tend to assume that the most typical member of a racial group is a heterosexual man. Thus, if you give people information that a man is not heterosexual, he deviates from this assumption—and in turn he seems less typical of the group to which he belongs.

In our article, we suggest that stereotypic Whitening—or the tendency to think of some men as “Whiter” when they’re described as gay—is driven, at least partly, by the fact that people stereotype gay men as privileged.

Despite the fact that gay men are actually more likely to face housing and food insecurity than their non-gay counterparts, our participants robustly characterized gay men as possessing upper-class attributes (for example, as being materialistic and sophisticated). Although we aren’t sure exactly where this stereotype comes from, a strong contender is the media, which often depicts gay men as privileged cosmopolitans who enjoy shopping and home makeovers (consider the gay men on Queer Eye, for example).

A consequence of this stereotype is that when men from under-resourced groups are described as gay (vs. not), they seem more affluent than they would have seemed otherwise. And because affluence, at least in the United States, is associated with being White, people in turn stereotype these men as “Whiter.”

At this point, it’s too early to tell what implications these stereotypes have for discriminatory behavior. But it’s possible that racial biases manifest differently toward gay men than they do toward heterosexual men. This and other research questions—like whether these distortions also apply to sexual-minority women—are at the forefront of where we plan to take this research next.

For Further Reading:

Petsko, C. D., & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2019). Racial stereotyping of gay men: Can a minority sexual orientation erase race? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 83, 37-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2019.03.002

Kang, S. K., & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2015). Multiple identities in social perception and interaction: Challenges and opportunities. Annual Review of Social Psychology, 66, 547-574.

Petsko, C. D., & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2019). Race-crime congruency effects revisited: Do we take defendants’ sexual orientation into account? Social Psychological and Personality Science, 10, 73-81.

Christopher D. Petsko is a doctoral candidate in social psychology at Northwestern University. He studies how stereotypes influence our perceptions of each other.

Galen V. Bodenhausen is the Lawyer Taylor Professor of Psychology and a Professor of Marketing at Northwestern University. He studies the fundamental mental processes underlying social attitudes, impressions, judgments, and decisions.